I go by Martin F. Martorell, though my ID says Martín Fernández Crespo, and in my neighborhood I’m just Martín. I’ve never bothered with elaborate pseudonyms.

I was born in Martorell (Barcelona) at the turn of the 21st century, just a few months after the Y2K scare. A few years later, my family moved to Ilche, a small village in Huesca where my earliest memories were made — such as throwing toys out of the window. But it wasn’t long before I ended up in Seville, the land of my family roots, where I’ve lived ever since.

My first brush with video games was anything but epic. No NES, no Spectrum, no Atari, no Sega, and definitely no Space Invaders in a smoky bar. My digital childhood began with a late-’90s PC that roared like a jet engine and had a bright turquoise desktop background. I had no idea what a processor was, or how much RAM it had. All I knew was that if I pressed the power button, my dad would yell at me.

The very first “video game” to enter our home was something my dad bought at a newsstand. It was called “Count and Sort” — a title as thrilling as it sounds. One of those educational games by Zeta Multimedia, the Spanish subsidiary of Grupo Zeta that, throughout the ’90s and early 2000s, published titles from DK Multimedia and other interactive software labels. The game starred a cheerful penguin and a friendly bear.

Around the same time, other masterpieces arrived: “My Amazing Human Body” and “Mia: The Search for Grandma’s Remedy” — also from Zeta Multimedia. They kept me entertained while making me believe I was learning something useful. They were the kind of products designed to sneak into households under the excuse of education — and they succeeded — though I still have a strange fondness for them.

Still, if I had to point to my first strong memory of a “proper” video game, it would be “Toy Story 2” by Traveller’s Tales for PC. I spent countless hours on it. Another title I hold dear is “102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Rescue”, another Disney release that left its mark on me — probably because it had a golf minigame with one of the greatest melodies ever composed by humankind.

Telling all this as my first gaming experiences may sound unheroic — even sad — from the outside, but those were my humble millennial beginnings, and I can neither escape nor disown them.

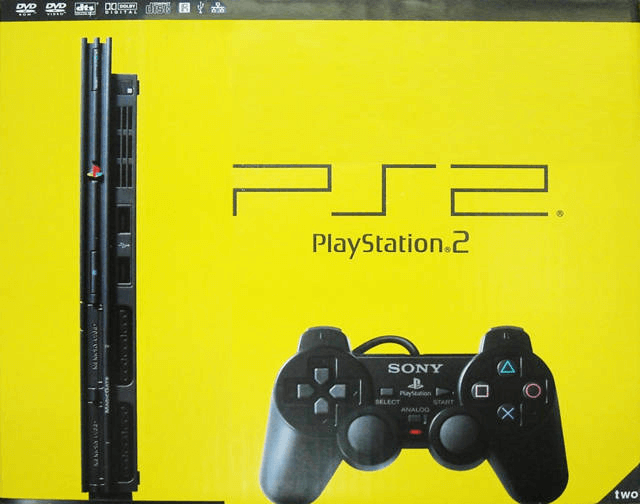

My first contact with a console came around 2005. By then I was living in Seville, and one day I visited my aunt’s house with my grandmother. My cousin was playing “Crash Bandicoot” on a PlayStation (decorated with a cool sticker from the movie A Bug’s Life) hooked up to a 14-inch TV. I knew the PlayStation 2 existed because I’d seen the ads, but I’d never seen an original PSX in action. That sparked a curiosity that, although I didn’t understand it at the time, planted a seed that would grow strong years later — an unconscious pull toward the history of video games.

By the late 2000s, like many families after the financial crisis, mine was in a modest economic situation. The idea of buying a brand-new console was simply out of the question. In my circle of friends it was much the same — most people had a PlayStation 2. I had one too: a Slim model, one of the early units prone to overheating and burning out their internal fuses. After several failed repair attempts, it ended up in a storage room, forgotten and dusty — like a broken promise or a botched science project.

However, I spent countless hours playing my Nintendo DS. In fact, because of Mario Kart DS, I didn’t have my First Communion. Yes, you read that right. I preferred to waste my time unlocking every Mirror Mode cup than sitting through early-age religious indoctrination in a faith I couldn’t care less about. If I had to suffer, it was going to be for first place in a race, not for the catechism.

I didn’t touch a Wii until 2010, nor an Xbox 360 until 2011. It was in 2011 when, thanks to good grades and some classic mother–son bargaining, my mom got me a Wii for my birthday — bundled with Mario Kart Wii and the plastic steering wheel. It was, without exaggeration, one of the most exciting gifts I ever received. The wheel was basically useless, but it made everything feel more impressive.

Wii consoles came with an intro video showing the possibilities of connecting to the internet. One feature — the one that caught my attention the most — was the ability to play classic Nintendo titles through the Virtual Console. The idea of accessing games from decades ago fascinated me… but of course, paying money for 20-year-old games wasn’t something my parents could justify. While searching online, I discovered PC emulation — my real gateway into the retro world.

I still remember the first time I launched “Super Mario 64” on the Project64 emulator. It felt unbelievably fresh and addictive, even though the game was already 15 years old. That title screen, that music, that open 3D world… I fell in love with the past. I realized there was something more authentic, more appealing than many of the games available at the time — or at least the ones I could afford.

Soon I discovered that old consoles and their games were, at the time, more affordable than current systems. So, without even realizing it, I began collecting retro video games at just 11 years old — much to my parents’ dismay.

My interest in video game history quickly deepened, especially after watching the documentary “Gameheadz: The History of Video Games”. I was particularly captivated by its first part, dedicated to the industry’s early years. I think it’s because I’ve always had a natural inclination to investigate the origins of everything around me, especially when it comes to beginnings. Added to this was my early fascination with the 1970s — a decade of profound social, political, cultural, and technological change — which left a decisive mark on my personality.

Not long after watching that documentary, I asked myself a question that would stick with me: How and when did those games arrive in Spain?

In 2013, I found my first clue on Marçal Mora’s RetroMaquinitas website: the Overkal — a Spanish console from the ’70s, a clone of the Magnavox Odyssey. I was stunned. Everyone talked about the “video game boom” in Spain as if it had begun in the ’80s, but the story started much earlier. This was proof that my question had an answer, yet it came wrapped in mystery and gaps in knowledge that I found irresistible.

I also wanted to own an Overkal — a dream I fulfilled at just 15 years old. It was a rather ironic contrast: my friends were transitioning to PS4s and Xbox Ones, while I was chasing down a strange, utterly obsolete console from over 40 years ago.

In December 2015, I launched a small site called prehistoricgaming.wordpress.com. The idea was simple but ambitious: to share my “research” and findings about the prehistory of video games — that little-explored period before the 1980s. It was a modest, homemade blog, but it was the first space where I began organizing everything I was discovering. I published articles. Well… I started articles. I had a habit of leaving them half-finished. Among those that did see the light of day was an early write-up on the Overkal.

In September 2015, I joined Asociación Sevilla Retro, organizers of the Retro Sevilla events held in Dos Hermanas between 2014 and 2019. From that group later came Arcade Planet, Spain’s largest arcade hall, where I volunteered doing maintenance and helping display classic machines. Few things compare to being surrounded by original arcade cabinets in full working order.

However, by age 17, I hit an existential crisis that pushed me to evolve. I completely stepped away from video games. I stopped playing, stopped researching. I became what I now call — with some irony — a pseudo-intellectual. I immersed myself in auteur cinema, vinyl collecting, heavy reading, and existential analysis. I swapped consoles for DVDs of Kubrick, Scorsese, Hitchcock, and Wilder films.

I got involved with the Seville European Film Festival — though I haven’t set foot there since 2019.

In parallel, cartridges gave way to vintage ’70s soul, funk, disco, and jazz fusion records. While that period distanced me from gaming, it gave me a valuable perspective: I applied the same obsessive curiosity to music and film. I dug into the history of artists, musicians, composers, producers, directors, screenwriters, actors, editors, cinematographers, and crew members, as well as recording studios, distributors, and historic record labels. That phase of intense cultural research shaped a core part of who I am today and explains much of my current methodology.

In June 2023, on a hot Seville night, as I tried to fall asleep, an old fascination resurfaced: the Overkal. I felt a sense of guilt and unfinished business for leaving that article incomplete. I realized I’d left something unresolved and decided to get back on track. I wanted to finish what I’d started as a teenager. Since then, I’ve returned to the archaeology of video games and the preservation of our gaming heritage with more energy than ever.

Today I’m 25 years old, an administrative technician, a collector, a self-taught researcher, and I dedicate myself to uncovering the forgotten history of video games — especially in Spain. I’m not a journalist. I’m not an academic. But I am persistent and patient. I aim to connect the dots no one else connects, to document what no one else documents, and to give voice to pioneers left out of the official narrative. I want to prove that with passion and a solid, consistent methodology, you don’t need credentials or pretension to earn credibility.

And it all began with an educational game from a newsstand… and a pirated PlayStation covered with an A Bug’s Life sticker.

Contact and social media

- YouTube Channel (my musical side)

- Telegram

- LinkedIn